Software development goals

As developers, we must set ourselves these objectives when dealing with the development of a software system.

Codebase

A single codebase from which to deploy separately.

Test

The unit tests must not be left out at all, they are fundamental for the success of the project because make the developer able to perform refactor necessary to improve the quality of the code, implement new usecase, or improve dependability of the software without fear of breaking something.

We provide test datasets, "Golden" datasets and/or data generators, we maintain these assets with the same importance with which we develop the code, this will allow us to act without fear of introducing regressions.

We plan integration tests with external services in addition to the unit tests.

Let's use continuous integration systems in order to capture as soon as possible regressions and / or bugs, we maintain the continuos integration system as if it were the very application we are developing.

Dependencies

All dependencies (libraries, infrastructures, services) must be declared explicitly and appropriately isolated, This is to simplify as much as possible the mental model that we build of the distributed system that we are implementing.

Making this mental model simple leads us to think in a more reliable way about the behavior of the system and to have better control over it throughout the project.

Configurations

The runtime configurations of our application must be managed with particular care, the system configuration must be homogeneous and operation friendly, as developers we must always place ourselves in the perspective of whoever is managing the system, let's always consider ourselves the user of the configuration system, but let's not trust ourselves and our internal knowledge of the system, create a simple, consistent and reproducible configuration mechanism.

External services

Let's consider external services as resources connected to a server, let's correctly define their interactions, let's foresee their multiplicity and/or unavailability.

Build, release, run

We clearly separate the steps of compilation, release and execution, the system must be compileable without having access to the final system where it will run, the artifacts produced by the compilation must be reproducible.

The release must correctly mark the artifacts as released and the software supply chain must be traceable.

Processes

Consider the software composed of a series of stateless processes, that outsource their state on a persistence system with the appropriate strategy (event sourcing, write ahead logs, databases, etc ...)

This allows us to gain in robustness and compartmentalization of failure.

Port binding

Let's make it clear ports are used by the system we are building, let's plan their use correctly and document their function.

Concurrency

We make our system capable of scaling horizontally across multiple processes from the very beginning.

Availability

We maximize the robustness of the system we are developing by planning acceptable start-up times graceful shutdown mechanism, it will be difficult to guarantee these properties if not foreseen from the beginning.

Equality between environments

We make the software system aware of the environment in which it runs (dev, test, prod) but we consider as much as possible the environments as equal.

We make sure we specialize the environments as little as possible.

Logs

We consider logs as event streams, we carefully plan what to log at what level in order to facilitate operations, monitoring, debugging and the discovery of useful information from log analysis.

Administration processes

We design and make available webapps and/or command line interfaces that allow us to interact with the system in an easy and operations friendly way.

Monitoring and metrics

We make the system ready for operations from its conception, we export metrics, monitoring, and health checks with the aim of making our system observable, Starting a process and then wonder if it has really done everything you expect is not acceptable.

Documentation

We create clear documentation for our system that is capable of:

- Encourage on-boarding of new team members

- Make it clear to system operators what to do and how to best manage the system

- Make it clear to users how to interact with the system

[!Warning] Documentation has a cost, which kind of documentation has to be produced should be agreed with the customer during sale, proof of concept project often produce only the minimum level of internal documentation required.

Code Review

We develop our system through a clear flow based on the concept of code review, we integrate the features in the release only after making a process of Merge Request and a review.

We encourage the growth of other team members by conducting Pair Programming sessions.

Programming languages

- Java as first choice for enterprise or data intensive applications

- Python as first choice for data science applications

Typescript for frontend

Scala has been deprecated, so we leverage it only for maintenance of existing code base or if the customer explicitely request it.

The use of other programming languages should be discussed with the architects, for example the use of python for the development of a back-end.

Best practices

Code formatting

Code formatting is essential to reduce merge conflicts.

There are some conflicts that have no legitimate reason to occur, including: mixed line endings (CR, CR+LF, LF), different indentation styles, variable code formatting conventions, and general code reformatting as part of an unrelated job.

Source control tools and IDEs can and must be configured consistently across all contributors to avoid conflicts. Wherever the tools support it, formatting style configurations must be included in the repository. This facilitates sharing and ensures consistency. Many modern tools support separate configuration at the project and user levels, thus supporting customization while having a shared configuration.

If there is no shared coding style, it is necessary to disable automatic formatting within the development environment.

To support the developer in ensuring the consistency of formatting within the project you can use tools to be integrated into the build process, for example in java you can verify the adherence of the formatting to the shared style through checkstyle.

For Scala we suggest to use scalafmt which can be easily configured placing a .scalafmt file in the root directory of the project: Intellij and visual studio code automatically ask you if you want to use the scalafmt configuration to format your code. An example of scalafmt configuration that we like a lot is available here.

For formatting Java code there a lot of alternatives, we found particularly easy to setup and use spotless. It supports various languages and for each of them various code formatting tools. We used it proficiently through a maven with the following configuration (placed under project.build.plugins):

<plugin>

<groupId>com.diffplug.spotless</groupId>

<artifactId>spotless-maven-plugin</artifactId>

<version>${spotless.version}</version>

<configuration>

<!-- optional: limit format enforcement to just the files changed by this feature branch -->

<ratchetFrom>origin/master</ratchetFrom>

<formats>

<!-- you can define as many formats as you want, each is independent -->

<format>

<!-- define the files to apply to -->

<includes>

<include>*.md</include>

<include>.gitignore</include>

</includes>

<!-- define the steps to apply to those files -->

<trimTrailingWhitespace/>

<endWithNewline/>

<indent>

<tabs>true</tabs>

<spacesPerTab>4</spacesPerTab>

</indent>

</format>

</formats>

<!-- define a language-specific format -->

<java>

<!-- no need to specify files, inferred automatically, but you can if you want -->

<!-- apply a specific flavor of google-java-format -->

<googleJavaFormat>

<version>1.7</version>

<style>GOOGLE</style>

</googleJavaFormat>

<!-- make sure every file has the following copyright header. optionally, Spotless can set copyright years by digging through git history (see "license" section below) -->

<licenseHeader>

<content>/* (C)$YEAR */</content> <!-- or <file>${basedir}/license-header</file> -->

</licenseHeader>

</java>

</configuration>

</plugin>

Remember that these are only suggestions and you must ensure they fit your project specific standards. If you see something that you do not like, propose a change!

Scala best practices

Scala is a very complex language with a lot of features... too many in some cases! Our Software Mentors have gone through a lot of mistakes and have seen too many horrible things happen, take advantage of them when you are approaching a challenging design solutions: they can help you to find the right way of doing the thing, or at least, make you avoid some of Scala pitfalls and unsound features.

A part from relying on Software mentors we kindly suggest you to read the following list of best practices that will avoid you a lot of headhaces.

Even if Scala gives you too much freedom, scalac can be your friend: it comes with a lot of arguments that let you catch at compile time most errors. It can also help you to avoid using controversial or too advanced features without realizing it. Based on Reccomended tpolecat scalac flags, we crafted our own list of recommended flags:

Scala 2.11

scalacOptions ++= Seq(

s"-target:jvm-${Versions.jdk}",

"-Xsource:2.12", // Enable some scala 2.12 features for scala 2.11

"-deprecation", // Emit warning and location for usages of deprecated APIs.

"-encoding", // Specify character encoding used by source files.

"utf-8", // Specify character encoding used by source files.

"-explaintypes", // Explain type errors in more detail.

"-feature", // Emit warning and location for usages of features that should be imported explicitly.

"-language:existentials", // Existential types (besides wildcard types) can be written and inferred

"-language:experimental.macros", // Allow macro definition (besides implementation and application)

"-language:higherKinds", // Allow higher-kinded types

"-language:implicitConversions", // Allow definition of implicit functions called views

"-unchecked", // Enable additional warnings where generated code depends on assumptions.

"-Xcheckinit", // Wrap field accessors to throw an exception on uninitialized access.

"-Xfatal-warnings", // Fail the compilation if there are any warnings.

"-Xfuture", // Turn on future language features.

"-Xlint:adapted-args", // Warn if an argument list is modified to match the receiver.

"-Xlint:by-name-right-associative", // By-name parameter of right associative operator.

"-Xlint:delayedinit-select", // Selecting member of DelayedInit.

"-Xlint:doc-detached", // A Scaladoc comment appears to be detached from its element.

"-Xlint:inaccessible", // Warn about inaccessible types in method signatures.

"-Xlint:infer-any", // Warn when a type argument is inferred to be `Any`.

"-Xlint:missing-interpolator", // A string literal appears to be missing an interpolator id.

"-Xlint:nullary-override", // Warn when non-nullary `def f()' overrides nullary `def f'.

"-Xlint:nullary-unit", // Warn when nullary methods return Unit.

"-Xlint:option-implicit", // Option.apply used implicit view.

"-Xlint:package-object-classes", // Class or object defined in package object.

"-Xlint:poly-implicit-overload", // Parameterized overloaded implicit methods are not visible as view bounds.

"-Xlint:private-shadow", // A private field (or class parameter) shadows a superclass field.

"-Xlint:stars-align", // Pattern sequence wildcard must align with sequence component.

"-Xlint:type-parameter-shadow", // A local type parameter shadows a type already in scope.

"-Xlint:unsound-match", // Pattern match may not be typesafe.

"-Yno-adapted-args", // Do not adapt an argument list (either by inserting () or creating a tuple) to match the receiver.

"-Ypartial-unification", // Enable partial unification in type constructor inference

"-Ywarn-dead-code", // Warn when dead code is identified.

"-Ywarn-inaccessible", // Warn about inaccessible types in method signatures.

"-Ywarn-infer-any", // Warn when a type argument is inferred to be `Any`.

"-Ywarn-nullary-override", // Warn when non-nullary `def f()' overrides nullary `def f'.

"-Ywarn-nullary-unit", // Warn when nullary methods return Unit.

"-Ywarn-numeric-widen", // Warn when numerics are widened.

"-Ywarn-unused", // Warn if unused.

"-Ywarn-unused-import", // Warn on unused imports

"-Ywarn-value-discard" // Warn when non-Unit expression results are unused.

)

Scala 2.12

scalacOptions ++= Seq(

"-deprecation", // Emit warning and location for usages of deprecated APIs.

"-encoding", "utf-8", // Specify character encoding used by source files.

"-explaintypes", // Explain type errors in more detail.

"-feature", // Emit warning and location for usages of features that should be imported explicitly.

"-language:existentials", // Existential types (besides wildcard types) can be written and inferred

"-language:experimental.macros", // Allow macro definition (besides implementation and application)

"-language:higherKinds", // Allow higher-kinded types

"-language:implicitConversions", // Allow definition of implicit functions called views

"-unchecked", // Enable additional warnings where generated code depends on assumptions.

"-Xcheckinit", // Wrap field accessors to throw an exception on uninitialized access.

"-Xfatal-warnings", // Fail the compilation if there are any warnings.

"-Xfuture", // Turn on future language features.

"-Xlint:adapted-args", // Warn if an argument list is modified to match the receiver.

"-Xlint:by-name-right-associative", // By-name parameter of right associative operator.

"-Xlint:constant", // Evaluation of a constant arithmetic expression results in an error.

"-Xlint:delayedinit-select", // Selecting member of DelayedInit.

"-Xlint:doc-detached", // A Scaladoc comment appears to be detached from its element.

"-Xlint:inaccessible", // Warn about inaccessible types in method signatures.

"-Xlint:infer-any", // Warn when a type argument is inferred to be `Any`.

"-Xlint:missing-interpolator", // A string literal appears to be missing an interpolator id.

"-Xlint:nullary-override", // Warn when non-nullary `def f()' overrides nullary `def f'.

"-Xlint:nullary-unit", // Warn when nullary methods return Unit.

"-Xlint:option-implicit", // Option.apply used implicit view.

"-Xlint:package-object-classes", // Class or object defined in package object.

"-Xlint:poly-implicit-overload", // Parameterized overloaded implicit methods are not visible as view bounds.

"-Xlint:private-shadow", // A private field (or class parameter) shadows a superclass field.

"-Xlint:stars-align", // Pattern sequence wildcard must align with sequence component.

"-Xlint:type-parameter-shadow", // A local type parameter shadows a type already in scope.

"-Xlint:unsound-match", // Pattern match may not be typesafe.

"-Yno-adapted-args", // Do not adapt an argument list (either by inserting () or creating a tuple) to match the receiver.

"-Ypartial-unification", // Enable partial unification in type constructor inference

"-Ywarn-dead-code", // Warn when dead code is identified.

"-Ywarn-extra-implicit", // Warn when more than one implicit parameter section is defined.

"-Ywarn-inaccessible", // Warn about inaccessible types in method signatures.

"-Ywarn-infer-any", // Warn when a type argument is inferred to be `Any`.

"-Ywarn-nullary-override", // Warn when non-nullary `def f()' overrides nullary `def f'.

"-Ywarn-nullary-unit", // Warn when nullary methods return Unit.

"-Ywarn-numeric-widen", // Warn when numerics are widened.

"-Ywarn-unused:implicits", // Warn if an implicit parameter is unused.

"-Ywarn-unused:imports", // Warn if an import selector is not referenced.

"-Ywarn-unused:locals", // Warn if a local definition is unused.

"-Ywarn-unused:params", // Warn if a value parameter is unused.

"-Ywarn-unused:patvars", // Warn if a variable bound in a pattern is unused.

"-Ywarn-unused:privates", // Warn if a private member is unused.

"-Ywarn-value-discard" // Warn when non-Unit expression results are unused.

)

Sometimes -Xfatal-warnings and -deprecation can get in your way, because you have to extend a class which has some abstract deprecated methods (from an external dependency). If you are on Scala 2.11 you should use the fantastic silencer plugin that will let you silence warnings in very limited parts of your codebase. If you are lucky enough to be working on Scala 2.12.13 you can instead resort to the built-in @nowarn annotation.

Documentation

[!Warning] Documentation has a cost, which kind of documentation has to be produced should be agreed with the customer during sale, proof of concept project often produce only the minimum level of internal documentation required

Why should I worry about the documentation

In simple terms, documentation helps people to do what they have to do.

Documentation helps users and teams:

- Consume less mental energy, work with adequate effort, preserving resources for more important tasks

- Minimize workload, onboarding of new team members takes place quickly and efficiently, they can start working right away.

- Improve your corporate brand, make it clear how you treat your external customers and internal employees by demonstrating support and help.

What is documentation?

Documentation is all you think it is: a set of documents. A compass for the end user. A point of reference for the software engineer in you. In a more technical space, documentation is usually text or illustrations that accompany a piece of software. These documents serve as a guide, explaining how a system works, how it acts and how to use it. Teams can refer to the documentation when talking about product requirements, release notes or design specifications. Technical teams can use the documents to detail the code, APIs and register their software development processes.

Externally, documentation often takes the form of manuals and user guides for system administrators, support teams and other end users.

All documentation should aim to achieve two main objectives:

- Informing Users

- Enable users to successfully accomplish something

Types of documentation

Team documentation

Team documentation helps to clarify the work that is being done so that teams can work as a team. These documents come in the form of project plans, team schedules, status reports, meeting notes and anything else a team might need to work functionally and efficiently. This type of documentation is detailed, ensuring that everyone stays in sync during the execution of a project.

Project documentation

The project documentation is, of course, project-specific and provides the necessary structure for product development. It includes proposals, product requirements documents, design guidelines or sketches, roadmaps and other relevant information needed for development, with contributions from project managers, engineers and all other participating actors.

System documentation

The system documentation contains information about code, APIs and other processes that allow developers to understand how to interact with the software, as well as limitations and requirements. Code snippets, such as REST request and response examples, are critical to this type of documentation.

[!Note] System documentation should always include a thorough description of how to configure the system, document all configuration keys with their meaning and type.

End User Documentation

User documentation is often the most visible type of documentation. It should be easy to read and understand, and updated with each new version of the software. It takes shape in "Read Me" documents, installation guides, administration guides and tutorials.

Choice of documentation to be produced

The documentation to be produced is specific to the project being carried out, it is necessary to reach consensus as a team on what should be documented and how, we should never neglect the needs of the customer regarding the documentation, if the customer does not give us adequate information about it is our responsibility to anticipate the requests by asking the customer to explain clearly what is expected, so as not to find ourselves having to produce quickly a type of document never seen before.

How to create the documentation

The documentation must be managed like any software artifact, better if versioned within the repository containing the source code, producing the documentation in markdown is a good starting point, if the customer asks us for documents in a specific format we can manage them by generating them from the markdown in the repository, this allows us to version the documentation with the code. If generating the documentation in this way is impractical, we can manage the documents in their native format but still commit them within the repository, thus recording their relevance to a specific state of progress of the software.

Take inspiration from this document and how the versions are managed.

Test driven development

Test-driven development (abbreviated as TDD) is a software development model based on the principle that automatic tests are created before the software that must be tested, and that the development of the software is oriented exclusively to the goal of passing the automatic tests previously prepared.

More in detail, the TDD is based on the repetition of a short development cycle in three phases, called "TDD cycle". In the first phase (called "red phase"), the programmer writes an automatic test for the new function to be developed, which must fail because the function has not yet been implemented. In the second phase (called "green phase"), the programmer develops the minimum amount of code necessary to pass the test. In the third phase (called the "grey phase" or refactoring phase), the programmer refactors the code to adapt it to certain quality standards.

Red phase

In the TDD, the development of a new feature always begins with the creation of an automatic test to validate it. Since the implementation does not yet exist, the creation of the test is a creative activity, as the programmer must establish in what form the functionality will be exposed by the software and understand and define the details.

This approach leads to the definition of more consistent and robust interfaces as it forces the developer to put himself in the shoes of those who will use the functionality, be it a developer who programmatically invokes APIs or an end user.

For the test to be complete, it must be executable and, when executed, produce a negative result. In many contexts, this implies that a minimal "stub" of the code to be tested, necessary to ensure the compilability and executability of the test, must be made. Once the new test is complete and can be run, it should fail. The red phase ends when there is a new test that can be run and fails.

Green Phase

In the next step, the programmer must write the minimum amount of code required to pass the failed test. It is not required that the code written is of good quality, elegant, or general; the only explicit goal is for it to work, i.e. pass the test. In fact, it is explicitly forbidden by the practice of the TDD to develop parts of code not strictly aimed at passing the test that fails. When the code is ready, the programmer launches again all the tests available on the modified software (not just the one that previously failed). In this way, the programmer can immediately see if the new implementation has caused pre-existing tests to fail, i.e. has caused regressions in the code. The green phase ends when all tests are "green" (i.e. passed successfully).

Refactoring

When the software passes all the tests, the programmer spends a certain amount of time refactoring them, or improving their structure through a process based on small controlled changes aimed at eliminating or reducing objectively recognizable defects in the internal structure of the code. Typical examples of refactoring actions include choosing more expressive identifiers, eliminating duplicate code, simplifying and rationalizing the architecture of the source (e.g. in terms of its organization into classes), and so on. After each refactoring action, the automatic tests are performed again to ensure that the changes made have not introduced errors.

Advantages

If you write the tests before the code, you use the program before it is even created. It also ensures that the product code is individually testable. It is therefore mandatory to have a precise view of how the program will be used before it is even implemented. This avoids conceptual errors during implementation. In addition, the tests allow developers to have more confidence during the refactoring of the code, as they already know that the tests will work when required; therefore, they can afford to make radical changes in design, being certain that in the end they will get a program that will always behave the same way (being the tests always verified).

The use of Test Driven Development allows not only to build the program together with a series of automated regression tests, but also to estimate more accurately the progress of the development of a project.

If an object oriented approach is adopted, the creation of the test as a preliminary phase exhorts the developer to necessarily structure the code in such a way as to make it testable, this automatically leads to an increase in the cohesion of the classes and a decrease in their reciprocal coupling, since in order to be able to access the possibility of mocking dependencies on other classes and/or services it is necessary to isolate them clearly.

Continuous Integration

Continuous integration - the practice of frequently integrating new or modified code with the existing code repository - should take place with such a frequency that there is no window of intervention between commits and builds, and that no errors can arise without developers noticing and correcting them immediately. Builds are commonly triggered at each commit in a repository, instead of being scheduled periodically.

Continuous integration is based on the following principles:

Maintaining a code repository

Obviously, a version control system associated with the project is required. All the artifacts needed to build the project should be placed in the repository. The convention is that the system should be buildable from a new checkout and not require additional dependencies.

Automating the build

A single command should have the ability to build the system. Build automation can also include deploying automation to development, testing and production environments. In many cases, the build system not only compiles binaries, but also generates documentation, web pages, statistics and artifacts for distribution (such as Debian DEB, Red Hat RPM, jar).

Automated testing

Once the code has been compiled, all tests should be run to confirm that the commit you are building from has not introduced any errors or regressions.

Keeping the build fast

The build must be completed quickly, so that if an integration problem is identified quickly.

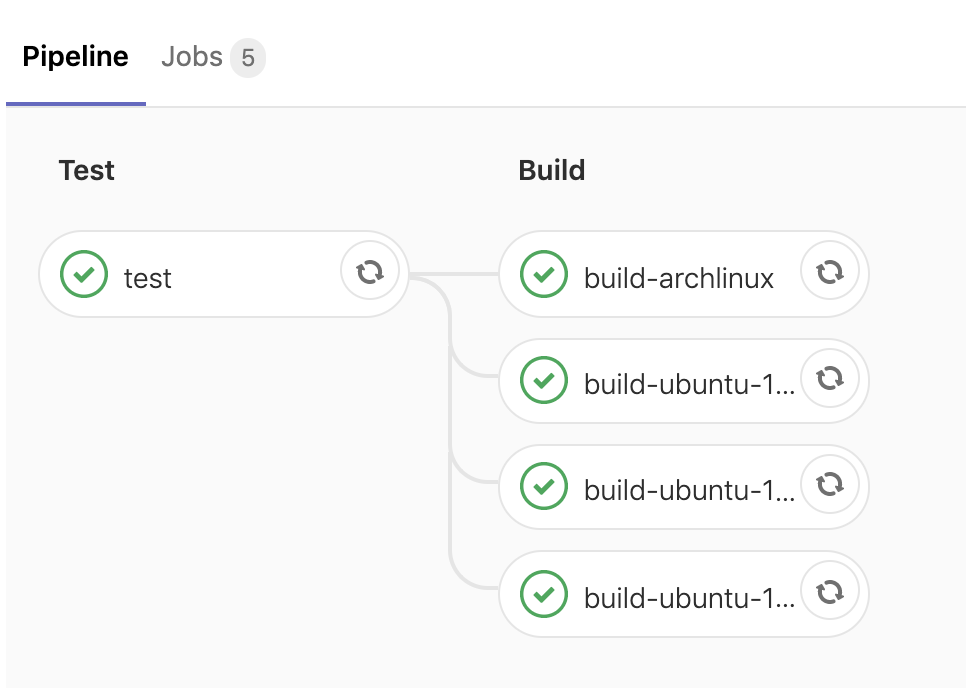

Continuous integration in AgileLab

The reference tool for implementing continuos integration pipelines is Gitlab.

In gitlab you can configure your own builds to be executed within docker container, it is therefore useful that each developer maintains container images oriented to the execution of reproducible and automated builds, within the project developer/docker you can maintain docker images (this can also be done at the level of individual projects) and use them later to make their own builds.

Gitlab CI example

stages:

- test

- build

image: python:2.7

test:

stage: test

script:

- pip install -r requirements.txt

- pytest

build-ubuntu-16.04:

image:

name: registry.gitlab.com/agilefactory/developers/agile-gitlab-cli/ubuntu-16.04:latest

entrypoint: [""]

stage: build

script:

- ./build-local.sh

artifacts:

paths:

- dist/lab-ubuntu-16.04

build-ubuntu-18.04:

image:

name: registry.gitlab.com/agilefactory/developers/agile-gitlab-cli/ubuntu-18.04:latest

entrypoint: [""]

stage: build

script:

- bash ./build-local.sh

artifacts:

paths:

- dist/lab-ubuntu-18.04

build-ubuntu-18.10:

image:

name: registry.gitlab.com/agilefactory/developers/agile-gitlab-cli/ubuntu-18.10:latest

entrypoint: [""]

stage: build

script:

- bash ./build-local.sh

artifacts:

paths:

- dist/lab-ubuntu-18.10

build-archlinux:

image:

name: registry.gitlab.com/agilefactory/developers/agile-gitlab-cli/archlinux:latest

entrypoint: [""]

stage: build

script:

- bash ./build-local.sh

artifacts:

paths:

- dist/lab-archlinux

Logging

Properly managing logging is a primary objective in the development of a software system, objectives of the proper implementation of logging are:

- Verifiability

- Observability

- Debuggability

A complex system is easier to manage if logging is done correctly and consistently.

it is necessary to standardize logging levels, assigning a precise meaning to each logging level, as the developer implements logging must be subject to code review because consistency is fundamental in generating value rather than overhead in having a logging infrastructure.

Logging levels

SLF4J defines five levels of message recording, from TRACE to ERROR. The guidelines for their use are very vague.

Note that all events with an INFO or higher level have a contract similar to the system API from an integration point of view: if they change, third party systems (e.g. monitoring systems) may need to be updated to work properly with the new system release. For these levels of logs, as far as possible system-internal jargon (references to the programming language, variable names) should be avoided as the target audience are end-users and system operators.

ERROR

This level serves as a general tool for errors. It should be used whenever the software encounters an unexpected error that prevents further processing. The software component that reports this error may attempt recovery operations.

Examples:

- Unrecoverable errors, OutOfMemoryError

- Inconsistency of the internal state of the application with any external systems

- Processing errors per request or work unit

The main targets are the monitoring systems and the system operators, as the reported events have an impact on the operational performance of the system.

WARN

This level is associated with events indicating irregular circumstances, from which we have a clearly defined recovery strategy that has no impact on system availability or performance.

A typical example of a candidate event is when a software component detects an inconsistency due to input data from external systems and takes corrective action to compensate for it.

The main audience for these events are automated systems, operators and administrators, as this level of messages indicates that the system is not functioning optimally or could herald future failure.

INFO

This level is used for events that constitute important state changes within a software component (such as initialization, shutdown, persistent resource allocation, etc.) that are part of normal operations.

Each software component should record at least four events at this level:

- when it enters the initialization phase

- When it becomes operational

- When the ordered shutdown starts

- Shortly before ending normally

The main audience for these events are the operators and administrators, who use them to confirm that the main interactions (such as rebooting components) have occurred correctly within the system.

DEBUG

This level is used by the developer to issue information of a strictly technical nature, such as intermediate processing results, it is useful to validate the proper functioning of the software under development.

This level of logs should not be active in production unless there is a specific need to diagnose a problem.

TRACE

This level is used by the developer to obtain information at a very fine level, for example it is possible to log at this level all the parameters entering a function, the execution times of the methods and other information of a very fine nature.

This level of log should not be active in production unless specific needs in the diagnosis of a problem.

Structured Logging

A recurring problem with log files is that they are written in the form of unstructured text. This makes it difficult to query them for any kind of useful information. As a developer, it would be useful to have the ability to filter all logs of a certain number of customers or transactions. The objective of structured logging is to solve this type of problem and allow further analysis.

For log files to be machine-readable, they can be written in a structured format that can be easily analyzed, such as json.

Structured logging can be used for different purposes:

Processing log files for analysis or business intelligence (A good example of this is processing logs of accesses to the web server)

Searching for log files: Being able to search and correlate log messages is very important for development teams during the development process and for solving production problems.

Example of structured logging:

{"pid":6253,"level":"INFO","time":"2018-05-13T17:52:25.147+09:00","msg":"User created article","user_id":123,"article_id":45}

Log aggregation

Especially in the development of distributed systems it is essential to provide a platform for the aggregation of application logs, it is not practical to have to manually retrieve logs from multiple machines and from multiple files with different formats, it is here that come into play a systems for log aggregation, ELK (Elasticsearch, logstash, kibana) is a de facto standard, developing by redirecting logs to one of these systems simplifies the diagnosis of any bugs and the collection of statistics.

For cloud ready applications it is a good idea to redirect the application logs to the reference service for the technology stack you are using in order to manage homogeneously the logs from all components of the application.

Formatting strings in logs

When emitting log lines you need to pay attention to how the strings to be logged are formatted, especially for very fine logging levels (debug, trace) because formatting strings for disabled logging levels becomes an expensive and useless operation, you need to use the idioms provided by the logging library you are using, for example with sfl4j you can use placeholders.

String user = "John";

log.info("Hello {}", user);

// the "Hello John" string is formatted only if the info log level for the current logger is enabled

or control explicitly if the log level is enabled

String user = "John";

if(log.isInfoEnabled()){

log.info("Hello " + user);

}

// the "Hello John" string is formatted only if the info log level for the current logger is enabled

in Scala it is possible to use call-by-name parameters, a logging trait that exploits this language capability is available in the agile-commons library.

Correlation ids

In multithreaded systems that process multiple requests at the same time it is usually difficult to reconstruct how the log messages are related to the processing of an input request, it is useful to assign an id to the input request to the system and to equip each log line with this id.

2019-09-03 15:31:29.189 INFO [903c472a08e5cda0] COLLECTING CUSTOMER AND ADDRESS WITH ID 1 FROM UPSTREAM SERVICE

2019-09-03 15:31:29.193 INFO [903c472a08e5cda0] GETTING CUSTOMER WITH ID 1

2019-09-03 15:31:29.198 INFO [903c472a08e5cda0] GETTING ADDRESS FOR CUSTOMER WITH ID 1

Monitoring

Monitoring is the process to gather metrics about the operations of an IT environment's hardware and software to ensure everything functions as expected to support applications and services.

Basic monitoring is performed through device operation checks, while more advanced monitoring gives granular views on operational statuses, including average response times, number of application instances, error and request rates, CPU usage and application availability.

Monitoring can rely on agents or be agentless. Agents are independent programs that install on the monitored device to collect data on hardware or software performance data and report it to a management server. Agentless monitoring uses existing communication protocols to emulate an agent, with many of the same functionalities.

For example, to monitor server usage, an IT admin installs an agent on the server. A management server receives that data from the agent and displays it to the user via the IT monitoring software interface, often as a graph of performance over time. If the server stops working as intended, the tool alerts the administrator, who can repair, update or replace the item until it meets the standard for operation.

Application level monitoring is one of the pillar of cloud ready applications, the application itself exposes structured data about its inner workings, this enables operators of the system to manage, observe and proactively inform the development team of issues, regressions and unexpected behaviors.

One of the leading application monitoring platforms at the moment is prometheus, there are libraries for all the main languages that are able to export application metrics in a prometheus compatible format.

An example prometheus endpoint responds with info similar to these:

# HELP hash_seconds Time taken to create hashes

# TYPE hash_seconds histogram

hash_seconds_bucket{code="200",le="1"} 2

hash_seconds_bucket{code="200",le="2.5"} 2

hash_seconds_bucket{code="200",le="5"} 2

hash_seconds_bucket{code="200",le="10"} 2

hash_seconds_bucket{code="200",le="+Inf"} 2

hash_seconds_sum{code="200"} 9.370800000000002e-05

hash_seconds_count{code="200"} 2

By collecting the reported data, dashboards and timeseries visualization can be built.

Serialization and schema evolution

Serialization is the process of translating data structures or object state into a format that can be stored (for example, in a file or memory buffer) or transmitted (for example, across a network connection link) and reconstructed later (possibly in a different computer environment). When the resulting series of bits is reread according to the serialization format, it can be used to create a semantically identical clone of the original object.

Schema evolution is the term used for how the store behaves when schema of the serialized objects is changed after data has been written to the store using an older version of that schema. Many serialization formats (like java serialization) do not support schema evolution, if the class definition changes data stored with the older definition becomes unreadable, this is often unacceptable and should be mitigated by the usage of a serialization format supporting schema evolution and/or by structuring the application from the very beginning to address the "schema evolution problem".

In the bigdata ecosystem popular serialization format are:

- Java Serialization

- Json

- Avro

- Thrift

Always prefer avro when designing big data applications for its compactness, bigdata tool support and for its clean schema evolution semantics.

[!Note] AgileLab opensourced Darwin an avro schema registry on github, please check that project documentation and use it pervasively any time you are using avro serialization, it is an important company asset and currently solves many pain point in working with binary serialized data while retaing the ability to evolve the schema

Benchmarks

A benchmark is the act of running a computer program, a set of programs, or other operations, in order to assess the relative performance of an object, normally by running a number of standard tests and trials against it.

Benchmarking is usually associated with assessing performance of software, software benchmarks are, for example, run against compilers or database management systems (DBMS).

Benchmarks provide a method of comparing the performance of various subsystems across different conditions.

AgileLab has a culture of "benchmark or it didn't happen", do not start wars on "immutable is slower than mutable", "java is slower than c", we are going to waste time, if you want to assess the performance characteristic of code use a benchmarking framework and measure it objectively.

[!Note] The developers gitlab group hosts a project related to microbenchmarks of code snippets, if you develop general microbenchmark please open a merge request there, the same concept can be used to develop project microbenchmarks inside the project repository, Enjoy!

Profiling

Often we need to diagnose where our software spends time in order to identify where is best to optimize to gain performance boosts, this is a time consuming and error prone process (in term of wasted hours optimizing a method for little gain) our effort should be guided by metrics collected with profiling tools.

Cpu profiling

The task of a profiler is to measure resources usage by a program (in our case, to measure CPU time consumption). In an ideal world results are not affected by a method of measurement used, but in reality they do. This is why several measurement approaches exist.

A profiler needs to record what functions were invoked and how many times it took to execute a function. The simplest way of obtaining this data is sampling. When using this method, a profiler interrupts program execution at specified intervals and logs the state of program’s call stack. The problem with sampling is that even with hardware support it’s not 100% accurate. Some function calls can fall down through `holes’ of a sampling grid, and will not be seen in a profile. But this usually means that these functions are not worth optimizing—CPU spent very little time executing them. The great benefit of the sampling approach is that it almost doesn’t affect program execution, so it can be successfully used in production environment.

Instrumentation is often considered as a more `precise’ approach to profiling. Doing an instrumentation means inserting a special code that performs calls counting or calculation of execution time into prologs and epilogs of functions. The problem with this approach is that it can seriously skew the results of profiling. Consider a function which takes just a dozen CPU cycles to execute and add another dozen of cycles due to instrumentation—now the instrumented function runs twice as long as the original version! And getting the current time is a system call which means that it will take a lot more CPU cycles to burn. That’s why some profilers (e.g. GNU gprof) usually instrument code only to record function’s call count—this is a relatively cheap operation, and measure function execution time using sampling. The other solution is to restrict instrumentation only to a selected subset of program’s functions.

Optimize hot methods first to instantly improve performance of the software you are developing.

[!Note] Use VisualVM cpu sampling or profiling each time you need to gain insights on what to optimize.

Memory profiling

When dealing with software running on the jvm we dread the infamous OutOfMemoryError, or the more destructive and heap dump inducing GC Overhead Limit Exceeded. We need tools to inspect the content of the heap and try to make sense of why the jvm garbage collector is not performing correctly its duty, it is fundamental to master heap profiling tool to be able to resolve this kind of errors.

[!Note] Use VisualVM memory sampling or profiling each time you need to gain insights on what is making your heap so difficult to manage

Tools

Build Tools

| Linguaggio | Tool | |

|---|---|---|

| Scala | Maven | the customer does not accept an SBT deliverable |

| Scala | SBT | the customer accepts deliverable based on SBT |

| Java | Maven | |

| Python | Setup tools |

Test Tools

| Linguaggio | Tool |

|---|---|

| Scala | Scalatest |

| Java | Junit |

| Python | Unittest |

Api Documentation Tools

| Linguaggio | Tool |

|---|---|

| Scala | Scaladoc |

| Java | Javadoc |

| Python | Docstrings |

Static analysis tools

https://github.com/mre/awesome-static-analysis

| Linguaggio | Tool |

|---|---|

| Scala | scalastyle |

| Scala | scalafmt |

| Scala | scapegoat |

| Java | Findbugs |

| Java | CheckStyle |

| Java | SonarJava |

| Python | pycodestyle |